The New Digital Folktale

Article by Laura Houlberg

In June 2020, Universal Pictures signed a 5-movie deal with Timur Bekmambetov, director, producer, and the film industry’s biggest advocate for a new type of storytelling format best known as screenlife. Films in the screenlife format take place entirely on computer screens, as the audience watches stories unfold through clicks, emails, video chats, internet searches, and digital ephemera. It’s a space very familiar to many, as the pandemic caused screen-time to bloom in the past year, drawing us into ever more intimate relationships with colleagues, friends, and family, mediated by pixels.

Arguably more impactful than screenlife’s aesthetic potential, according to Bekmambetov, is its ability to “organize a new moral landscape” for our increasingly virtual lives. We have thousands of years of stories “based on mythologies and religions and history lessons,” about how to live well with others in the physical world, but Bekmambetov asserts that many of these rules don’t function the same in virtuality. Screenlife stories will be the new folktales of the MySpace to TikTok generations, incorporating themes like digitally shrouded identities, code gone awry, and the power of niche community building.

One of these emerging folktales is the subject of two screenlife films, “Hello Nebula? It’s me, Margaret” (2015) by Rachel Stuckey, and “Watching the Pain of Others” (2018) by Chloé Galibert-Laîné. Both films orbit private anxieties about health and mortality, where the characters’ alienation from typical institutions drives them to find validation, expertise, and community online, eventually burrowing so deeply that they placate their fears with anti-government conspiracies.

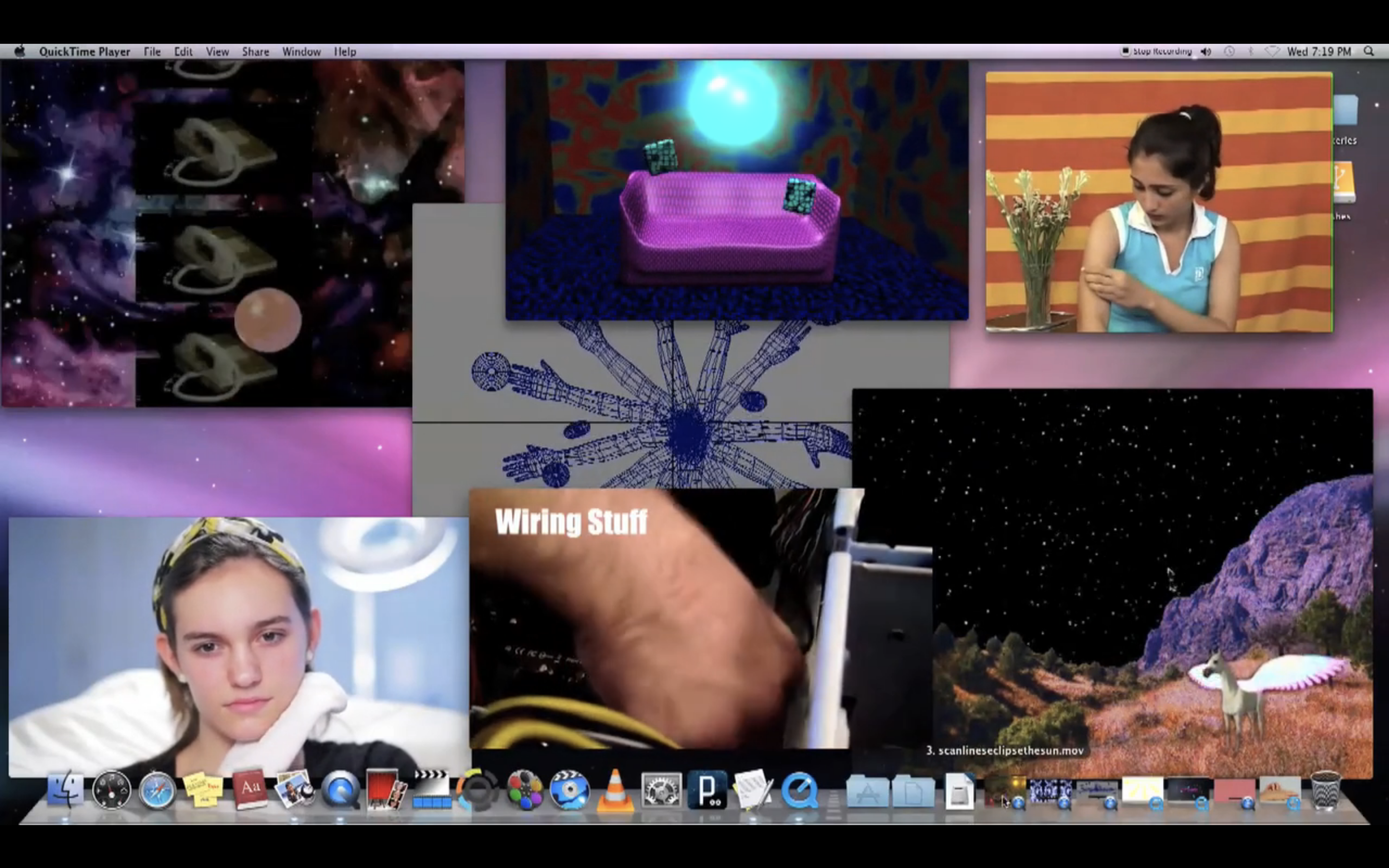

Rachel Stuckey’s “Hello Nebula? It’s me, Margaret” is a desktop-based musical, incorporating original songs, “How To” found-footage, stock photos, and bizarre advertisements. It begins with a call from Margaret to “Nebula,” a character represented by images of rolling, dusty cosmos as a stand-in for the universe itself, to report that she has a strange rash filled with colorful wires. Margaret, frustrated with Nebula’s inability to provide neither explanation nor comfort, turns to an online community of people with identical rashes, who offer validation and belonging, as well as a conspiracy theory that the wires are placed into their bodies by the government for surveillance.

Stuckey’s film, while campy and exaggerated, is inspired by a real community. Morgellons, “a self-diagnosed, scientifically unsubstantiated skin condition in which individuals have sores that they believe contain fibrous material” has a decade-old community online of mostly women who claim to be afflicted. It takes just a few clicks to stumble upon a treasure trove of user-uploaded videos documenting alleged evidence of the disease. It is this archive of videos that Chloé Galibert-Laîné’s film “Watching the Pain of Others'' delicately examines, as we become familiar with the stories of some of the women that we can imagine Stuckey’s Margaret has bonded with online.

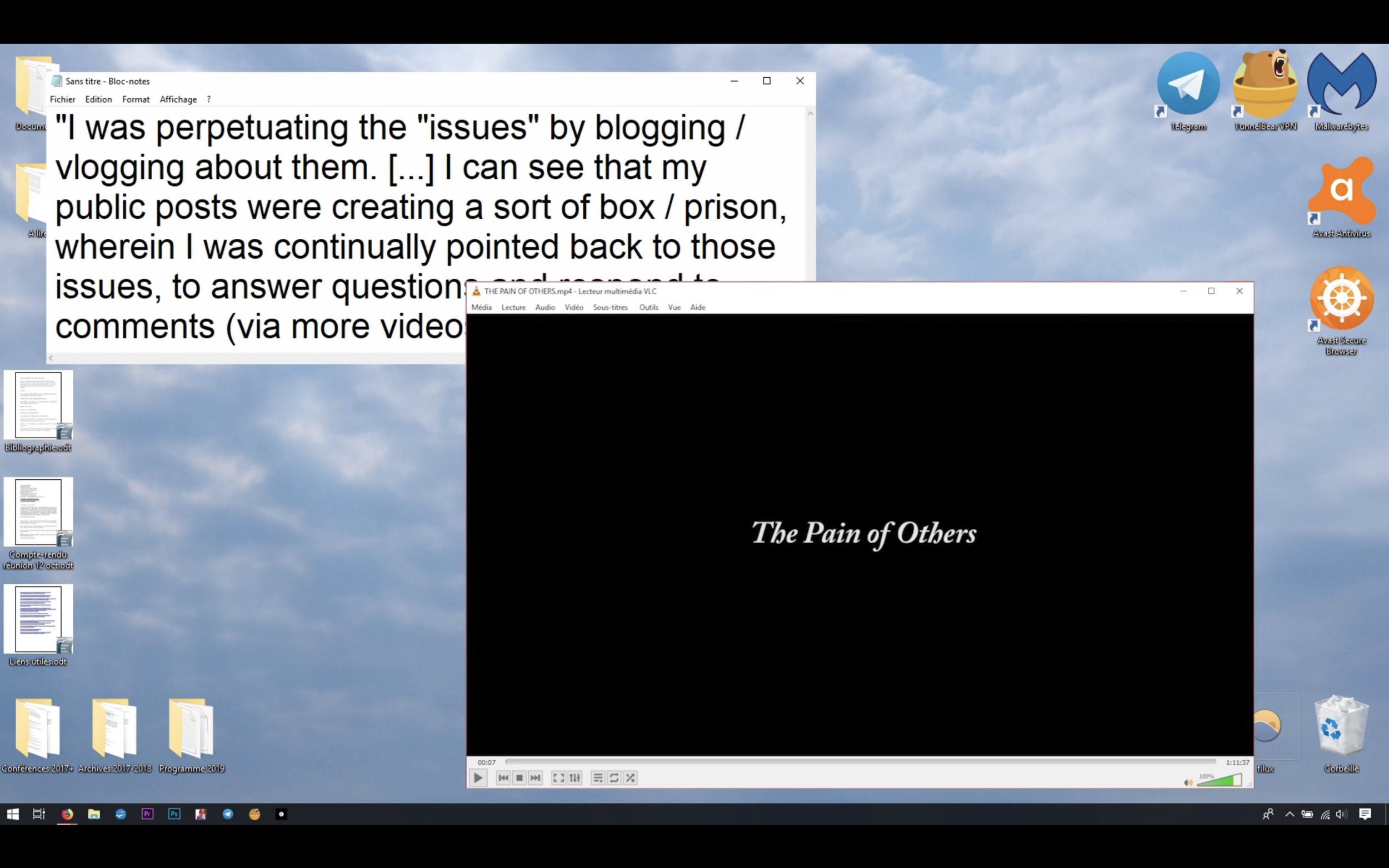

Appropriately titled, “Watching” documents Galibert-Laîné’s experience viewing, “The Pain of Others” (2018) by Penny Lane. Lane’s documentary is a collage of interviews with doctors and authorities, spliced with personal testimonies by Morgellons-afflicted Youtubers. Employing the same hyperfocus that the women experiencing Morgellons take to their own bodies, Galibert-Laîné dissects the film shot by shot, referring to her video editing software as her “operating table.”

After being immersed in the footage for some time, Galibert-Laîné notices symptoms on her own body strikingly similar to Morgellons. “This is how Morgellons gets transmitted,” says Galibert-Laîné, implying the “disease” spreads through exposure and empathy. “Rarely has talking about the ‘virality’ of online images been so relevant,” she remarks. Even one of the women from Lane’s documentary, Tasha, points out the online nature of her community, and by extension, illness. Galibert-Laîné remarks, “she says that every view, every click by every YouTube user has contributed to her pain by turning her disease into the condition for her social existence.”

Galibert-Laîné outlines this motif: “Fundamental loneliness, the need to communicate, to the point of ridicule, to the point of sickness.” Both films use Morgellons in the context of screens to address these contemporary anxieties: Our humanness merging with technology has made clumsy cyborgs of us all. Anxiety about health, perhaps due in part to the inaccessibility of healthcare in the U.S., has driven countless people to find alternative expertise and treatment for their illnesses. A gendered obsession with the functioning and appearance of the body has materialized against the backdrop of Instagram-perfect, pore-less models cluttering our visual fields online. Isolation, and its sister, loneliness, silently rule late-capitalism, accompanied and emboldened through surveillance by a pair of large all-seeing eyes belonging to the government and Big Tech.

Look no further than QAnon as an urgent example of these anxieties and their physical manifestations. QAnon followers, largely white and straight, refuse to face a nuanced and complex changing social culture, instead choosing to participate in the “Q” conspiracy theory, where reality dissolves and in-groups rule, anyone can be an “expert,” and the complicated implications of history are brushed away with deep government conspiracies about pedophilic cults, mystically revived dead Presidents, and rampant human trafficking. As QAnon wobbles into the physical world by electing their supporters to office, firing rifles into pizzerias, and even storming the Capitol, addressing the conspiracy at its source — the screen — is imperative.

Galibert-Laîné says of Lane’s film, “The Pain of Others”, “it keeps the imprint of a certain state of the world. A world where our exhibitionist and voyeuristic impulses, which by themselves are nothing new, are superimposed to an algorithmic logic, which amplifies them, and gives them a market value.” The screen is a shore, and like water forming ravines through a landscape, the possibilities of the world are pushed to us through the carved paths of algorithms, ensuring that only the possibilities we are assumed to desire are those most likely to reach us. Galibert-Laîné provides a sketch of our issue: “On the internet there is indeed a ‘we’ facing the spectacle of other people’s pain, but it is not the ideal ‘we’ of a community united through empathy.”

Screenlife’s potency lives in its potential to create an online community united with empathy. “When you see the character’s screen, it looks like you’re inside somebody else’s mind. You see every mistake, every subconscious act, whatever. You see a lot of secrets.” By showing us the decisions and interactions that occur behind our online personas, the stories behind the posting, unfriending, and ceaseless searching, we can teach online literacy, cultivate community united by genuine empathy, and sharpen new tools of digital discernment. As virality emerges as the dominant mode of cultural proliferation, both as the pandemic rages on and forces us into virtuality, and “viral” images and stories govern our social language, addressing it through digital storytelling is as urgent as ever.

Image credits: screenshots from “Hello Nebula? It’s me, Margaret” (2015) by Rachel Stuckey, and “Watching the Pain of Others” (2018) by Chloé Galibert-Laîné.